Do I Need to Be 'Objective' About Abortion?

On journalists, objectivity, and the bodily autonomy of 51 percent of the population.

You’re a free subscriber to Wait, Really? For the full experience, become a paying subscriber.

There have been many times as a journalist that I've been required to withhold my views, or refrain from exercising those views publicly. In a job interview, I was quizzed on whether I’d attended the Women’s March, which of course I had, but with a notebook not a picket sign, which made it OK. I've been cautioned that my reporting on the wage gap could be perceived as "activism,” while simultaneously being encouraged to mine my own experience with such inequity in my writing. When I was gender editor, I was frequently asked if the mere existence of that role was biased — and sometimes I wondered if my bosses questioned the same.

I've accepted at this point that my view on “objectivity” will not always align with those who pay me for my work; that I believe it’s possible to be fair in my reporting and also have opinions about the things I cover (in fact, I’d argue, this enriches my work); and that acknowledging inherent inequality in society does not render me biased, but clear-eyed about the state of the world. Of course, I also like to remain employed, so like many journalists who work for mainstream news outlets, I have learned to temper what I say (and write).

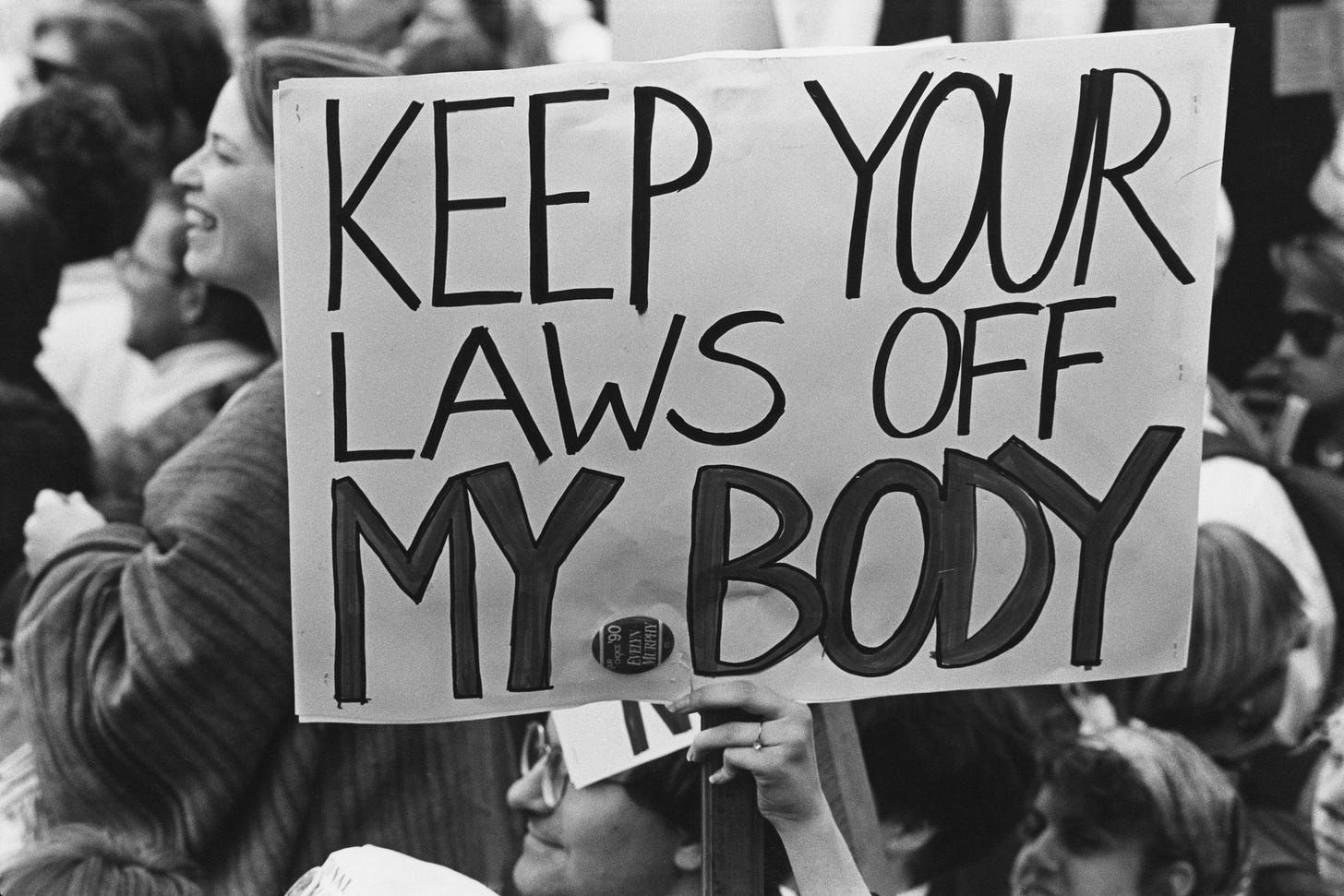

That’s gotten particularly difficult in the wake of the Supreme Court’s overturn of Roe v. Wade — a subject that, while politicized to the extreme, deals with the fundamental ability of a woman to control her bodily autonomy. I happen to see that as an objective human right. Yet many journalists are not allowed to say that.

Even before the Supreme Court ruling, as Vanity Fair reported recently, organizations from The New York Times to Gannett to NPR and the Associated Press had reminded their employees to keep their abortion opinions to themselves. That is: no tweeting, no attending rallies, no taking a “side,” no expressing opinions that could put a publication’s perception of "objectivity" at risk (key word: perception). As the editor of Axios told staffers in a memo, after the draft decision was leaked: “Abortion is a human-rights issue that has become a highly politicized topic … So it seems impossible to march—or tweet opinions—and not be perceived as picking a political side.”

Twitter embed isn’t working so linking here. Sanders is a journalist and former NPR host.

Political sides are not reality, of course. And Axios, as Vanity Fair noted, is an interest case study in that the outlet took a different position during the height of Black Lives Matter protests — giving staff permission to exercise their right to protest and offering to cover bail should anyone be arrested doing so.

Human rights are not a zero sum equation. But what happens when these things intersect — which, well, of course they do? Which rights are considered fundamental enough that even journalists can openly speak in favor of them, and which are not?

This question has come up repeatedly over the past few years as reporters try to figure out how to navigate the increasingly public nature of their personal lives with, at times, the restricted nature of their jobs. Black reporters in particular have led a movement to question the view-from-nowhere tradition of journalistic objectivity — including Wesley Lowery, whose tweet you see below, and who made his name covering racial injustice for the Washington Post only to leave after they threatened to fire him for expressing his views on Twitter.

Wesley's full Twitter thread on this subject is worth reading.

There are nuances, of course. And yet it's interesting, and blurry, to think about where the lines are, as the basic rights of certain groups — from racial minorities to trans people to women — become increasingly politicized. If I am an immigrant, and I believe in fundamental human rights for immigrants — and state that belief out loud — does that make me a bad journalist? If I'm a journalist who is a woman, and I don't express my support for women to control their reproduction, does that make me a bad person? How do we square the idea that, in some realms, "lived experience" is seen as an asset — a way to add perspective and nuance to our work — while in others, it's perceived as something to hide? Is that even possible?

In my first journalism job, in college, for a now-defunct Seattle daily, I remember covering the legalization of gay marriage in Canada — and being asked by my editor to get a quote from the “other side,” somebody who didn't just oppose the law but opposed gay people's existence. I called a conservative pastor, who believed that homosexuality was a sin, in order to present a "balanced viewpoint" to the story. It ran on the front page, and I’ve never forgotten that detail.

A few years later, after same-sex marriage became the law of the land, and I was covering efforts to expand it on a statewide level for Newsweek, the thinking had changed: I could report on young gay activists who were galvanizing their communities, and the divisions between them, without having to give air space to an argument against same-sex marriage. We had reached a point, it seemed — and perhaps this was a very brief point, given the direction this country seems to be moving in — when the rights of gay people to exist did not need a detractor, and for this magazine, anyway, I was free to state that belief out loud.

At what point does the bodily autonomy of 51 percent of the population get to be a subject that doesn't require "the other side”?

(Barbara Alper/Getty Images)

So Much News, and One LOL:

Jan. 6 Hearings: Cassidy Hutchinson, a 26-year-old woman, did what the grown-ass men of the Trump White House would not. Here are six takeaways from her testimony.

Behind bars for sex trafficking: R. Kelly was sentenced to 30 years in prison. Ghislaine Maxwell was sentenced to 20 years in prison.

More on Roe: Men rush to get vasectomies. Legal confusion. What to do about all those period-tracking apps. The economic implications for male partners.

Corporate ‘allyship’: A growing number of companies have pledged to pay for employees to travel across state lines for abortions. At least 11 of the big ones also helped elect the conservative justices who made those pledges necessary, a New York Times analysis revealed.

On the aging female form: In her Substack newsletter, It’s Not Just You, my pal and longtime editor Susanna Schrobsdorff writes beautifully on watching Emma Thompson in HULU's “Good Luck to You, Leo Grande” — which, she writes, asks us to “reconsider how we see our lumpy, imperfect selves.” Read it here.

'Why do my students call me a goat?' On Reddit, an 8th grade math teacher adorably asks why her students keep calling her “a goat,” to which the internet explains they likely mean G.O.A.T., or Greatest of All Time, to which the teacher replies: “OMG I am in tears!!! I can’t believe they were complimenting me this whole time!!!” <3

Do You Know a 13-Year-Old?

Before I forget! I'm working on a project about teen life at 13, and we are looking for participants. Do you know a 13-year-old who might be interested in talking about life n teen stuff n social media and mental health with me and The New York Times? Have them fill out this form! (And feel free to share that link.)

Happy holiday weekend....

This message, shared by a friend on Facebook, seems apt. You can find me face down in the sand somewhere. ⛱⛱⛱

⏩ Forward this newsletter to a friend or sign up to get it to your inbox.

💬 Have thoughts to share? Email me at supwaitreally@gmail.com. (You can also just reply to this email.)

🙋🏻♀️ Follow me on Instagram or learn more about my writing and books here.