Photographing the Brutality, and Humanity, of War

A conversation with Pulitzer-winning photojournalist Lynsey Addario

You’re a free subscriber to Wait, Really? For the full experience, become a paying subscriber.

You have probably seen her work even if you don’t know you’ve seen her work — like the image below, taken in the early days of the war in Ukraine, as civilian volunteers prepared to take up arms and fend off Russian troops.

Up until that point, much of the visual coverage of the war had depicted men in combat gear, President Zelensky in his army green, and bloody chaos. But this image, of a schoolteacher named Julia, weeping as she waited to be deployed to Kyiv as a volunteer fighter, rifle clutched between her legs, was haunting.

Julia had been handed that gun two days prior. She didn’t know how to use it. But like many Ukrainians, she felt it was her duty to go and at least try to fight. Lynsey Addario, who was inside the transport van as Julia waited, captured the shot.

Addario, 48, has said her work aims to document the horror of war and conflict, as well as the humanity of those who are living through it. She’s become something of a master at it. She spent a number of months covering the war in Ukraine for The New York Times, and it's not unlikely she will return. She has also covered nearly every major conflict and humanitarian crisis of the past two decades, from the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, where she won a Pulitzer Prize, to famine in Yemen and genocide in Darfur.

Basra, Iraq, 2003: An Iraqi woman walks through a plume of smoke rising from a massive fire at a liquid gas factory as she searches for her husband.

I’ve had the pleasure of working with Addario a few times over the years, on domestic stories about undocumented pregnant mothers in Texas and women training to become marines in Paris Island, S.C. I have always followed, and been grateful for, her work from afar. So I was both relieved to know she was home safe and delighted to learn that Addario's work is the subject of a retrospective at the School of Visual Arts, which runs until December.

The exhibition, which is free and open to the public, spans almost 25 years, from playing with shutter speeds as a teenager growing up in Connecticut, to her first series for the Associated Press in the late 1990s, on trans sex workers, to her coverage of Afghan women under the Taliban.

I had about a million questions I wanted to ask Lynsey, but here are excerpts of a few she answered in advance of her show — as well as some of the images featured in it.

Afghanistan, 2009: Noor Nisa, 18 (right) was pregnant; her water had just broken. Her husband was determined to get her to a hospital in Faizabad, a four-hour drive from their village. Here, she is stranded with her mother in the Badakhshan Province.

You’ve been shooting for over two decades, in extreme conditions and conflict regions. You’ve been kidnapped, thrown out of a car, ambushed by the Taliban, but you keep going back. Why?

Lynsey Addario: The simple answer is that I feel strongly about the importance of journalism, and that photojournalism isn’t simply a job, but my life. I believe that the work of journalists — and especially in war zones which are not easily accessible to politicians and world leaders — holds policymakers and people in positions of power accountable to their decisions, to the policies they carry out. Our stories and photographs are a collective testimony of people’s voices and experiences on the ground, and eventually serve as a record of history.

Ukraine is a perfect example, where Russian President Putin’s public statements have repeatedly been contradicted by journalists on the ground. For example, Putin has repeatedly said his troops are not targeting civilians, but then we see the evidence in Bucha and the family I witnessed getting killed in an artillery strike while crossing the Irpin Bridge, a known civilian evacuation route. This example very clearly explains why I risk my life. On a lighter note, I think I just love people, and learning about culture and traditions and current affairs with every assignment I photograph.

Ukraine, 2022: A Ukrainian mother with her newborn in a basement maternity ward on the outskirts of Kyiv in March 2022.

What do you look for in a photo?

I am trying to tell stories with images, so ideally, each image can convey something to a reader or viewer. Within the individual image, I am trying to capture emotion, beautiful light (if possible), and compelling composition so people are drawn to the photograph and drawn into the story I am trying to tell.

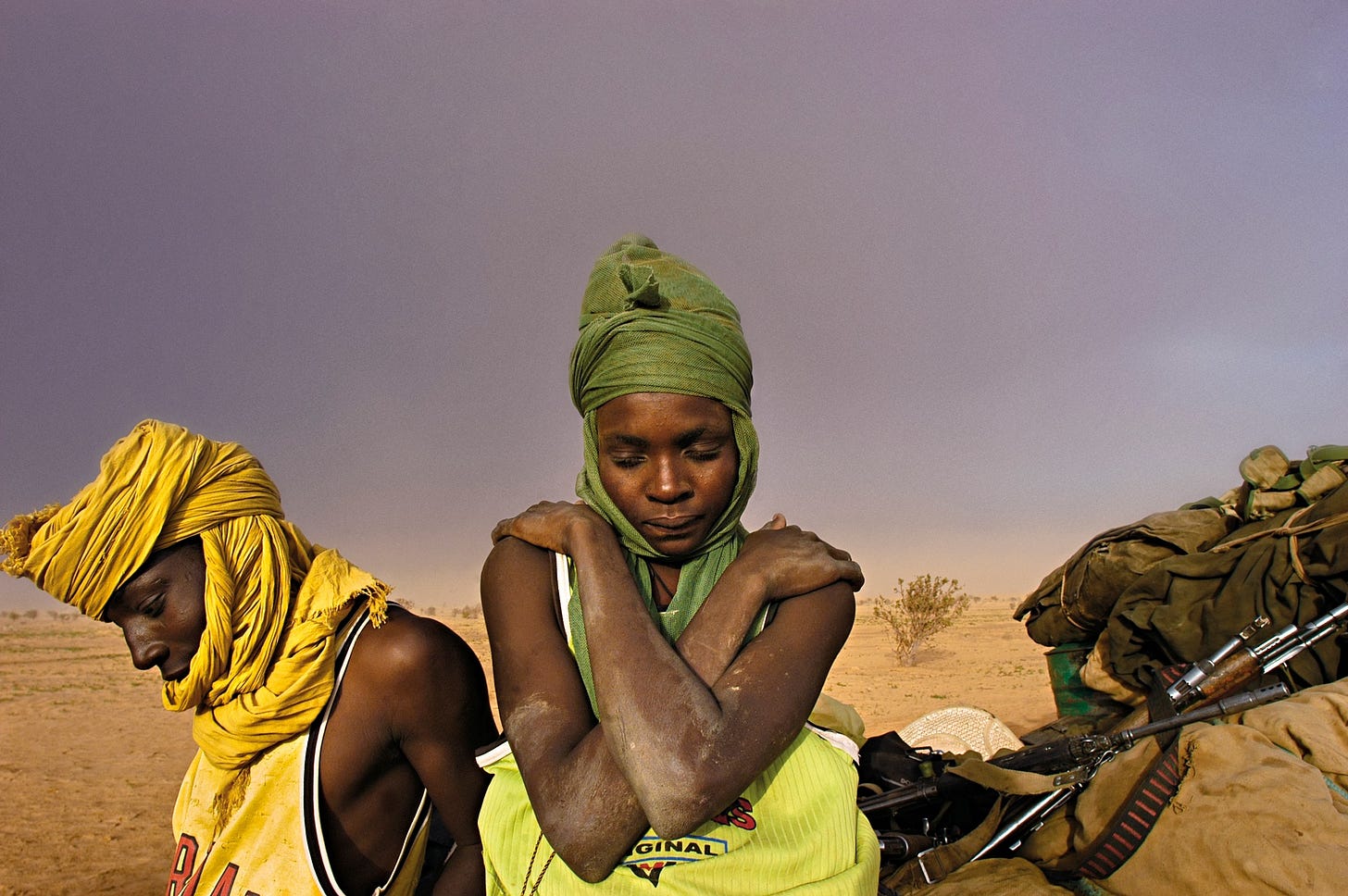

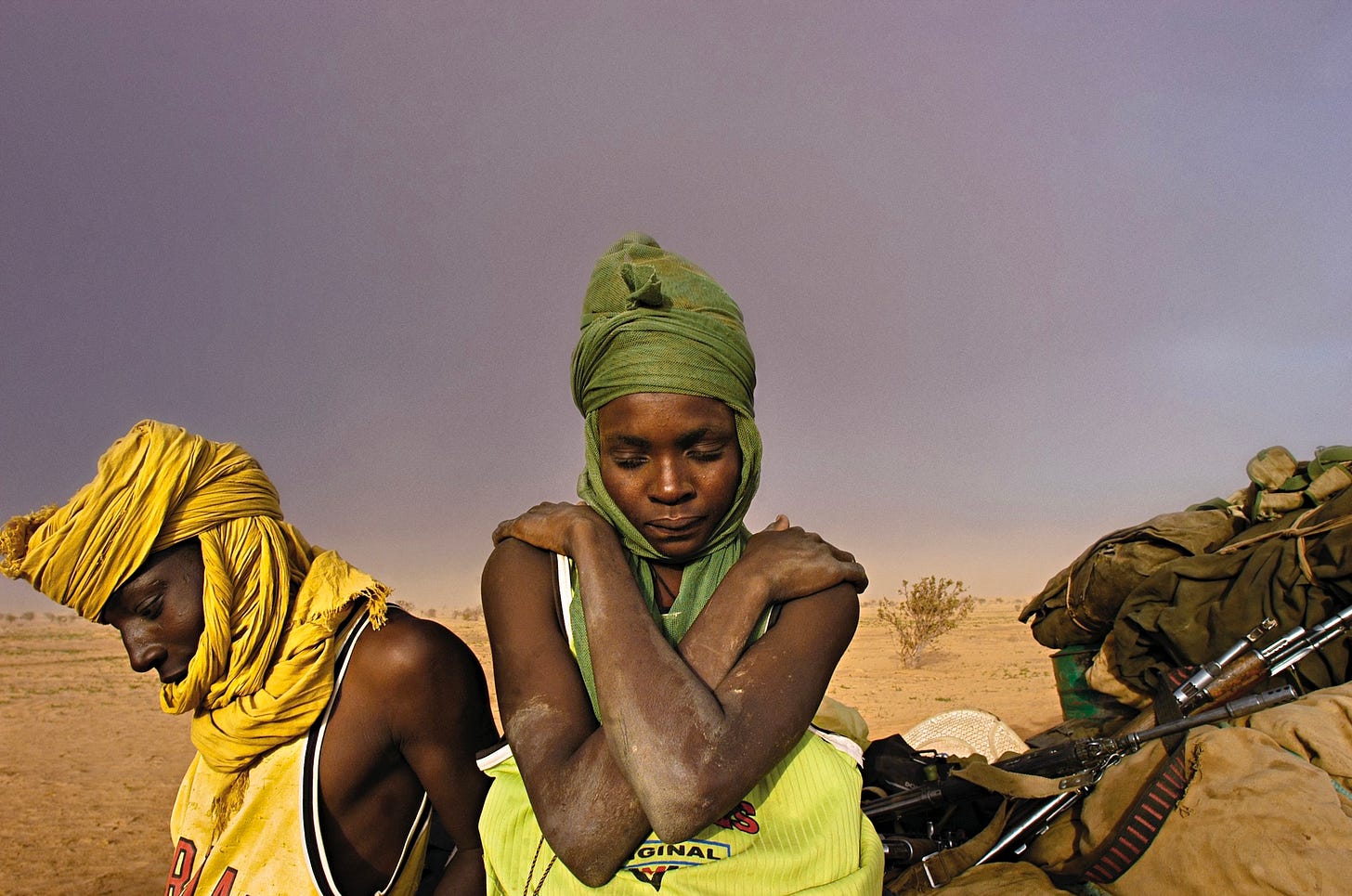

Sudan, 2004: Soldiers with the Sudanese People’s Liberation Army wait for their truck to be repaired as a sandstorm approaches in Darfur.

What was the hardest assignment of your career?

That’s a difficult question. Most assignments are difficult by virtue of the amount of pressure I put on myself to do a good, thorough job, and then having very little time to familiarize myself with a story and tell it accurately and in a profound way. Even 25 years into this career, I still get incredibly stressed before each trip and wonder if I will be able to do justice to a story. There are the stories which take an emotional toll, and those which drain me physically.

Photographing the death of Marieke Vervoort by Euthanasia in 2019 was one of the most difficult stories I have ever done. (Editor’s note: You can see the photos and read the story here, and learn more Lynsey's experience on the project here.)

I spent nearly three years with Marieke leading up to her death and developed a close relationship to her — perhaps too close. Over the years, I spent many days and nights photographing her, but also helping and taking care of her when no one else was around and she started having seizures. I was constantly struggling with my role as a journalist, but also as a friend.

Ethiopia, 2021: Eyerus, 40, poses for a portrait in a safe space for victims of sexual assault in the Ayder Hospital in Mekele,Tigray, Ethiopia, in May 2021.

So many of the people you photograph are in incredibly vulnerable situations. How do you build trust and get them to open up? How do you endure seeing so much suffering?

If the story is a story where I have some time to develop relationships, I work on building those, and on being transparent that my goal is to tell their stories in the most honest, unvarnished way. I think people can sense that I am dedicated, genuine and empathetic, and that I care deeply about presenting the most intimate, accurate depiction of whatever it is someone is going through. I endure the hardships I witness because I allow myself to feel and express emotion, and I am inspired by the people I photograph, who consistently teach me the power of resilience.

Lynsey Addario’s work is on display now until December 10 at the School of Visual Arts in Manhattan. It’s free and open to the public.

What Else I'm Reading:

What's wrong with America's teens? Article after article tells us that teenagers aren’t doing well without putting their finger on what's actually wrong. A clinical psychologist on what her teenage patients have to say about it, and what she links we can learn. [NY Times]

'We Left Iran in 1979. I Should Be There Now.' Neda Toloui-Semnani is one of thousands of Iranians watching protests engulf her country from afar after the death of 22-year-old Mahsa Amini. The country is at an inflection point. [NYMag]

The first all-female Lebanese metal band. A new documentary about the band, Slave to Sirens, is out now. 🤘🤘 [The Guardian]

"Vibe planning" is what I'm going to call canceling all my plans when I don't want to go out from now on. [SFist]

⏩ Forward this newsletter to a friend or sign up to get it to your inbox.

💬 Have thoughts to share? Email me at supwaitreally@gmail.com. (You can also just reply to this email.)

🙋🏻♀️ Follow me on Instagram or learn more about my writing and books here.

Jessica! I am so pleased you are on Substack! You raise the conversation 19 inches with your very presence!!!

What an inspiring and interesting interview - thanks for sharing.