For a certain breed of millennial like me, Tina Fey’s “Mean Girls” was gospel — a movie turned cult phenom that put names and labels to the kind of bullying that any woman who’d been to middle or high school would recognize.

The beauty of that film was that it got at just how vicious, but coded, the dynamics among girls could be: full of slights so subtle and underhanded that they had eluded social scientists for decades. For a long time, researchers just thought girls didn’t bully.

Then in the early aughts, a handful of books — including Rosalind Wiseman’s “Queen Bees and Wannabes,” and my pal Rachel Simmons’ “Odd Girl Out” — brought the concept of girls’ relational aggression into the mainstream. And that kind of aggression, it turned out — with its manipulations and exclusions and rumor-spreading and death stares from across the lunchroom — also happened to make for great comedy.

But much has changed in the 20 years since. Adults and teenagers alike are more aware of the importance of inclusivity and more attuned to the seriousness of subjects that used to be treated as fodder for jokes. So when Fey returned last month with her musical movie “Mean Girls” — a Gen Z update — it was inevitable there would be some changes.

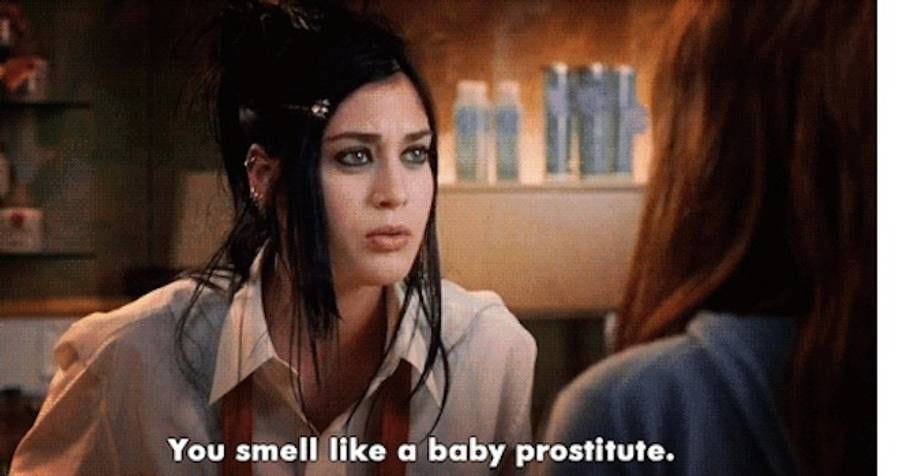

The cliques at North Shore High still include the theater kids and the Plastics, but they are no longer segmented by race; and Coach Carr, the P.E. teacher now played by Jon Hamm, is most definitely not making out with any students. Gone are the jokes about Janis Ian being a lesbian — because “even Regina would know what wouldn’t fly,” Fey said in an interview — instead, the beloved goth misfit, whose sexuality was ambiguous in the original (she reveals at the end that she’s “Lebanese”) is now out as queer.

Regina no longer uses the R-word or calls her friend “dyslexic”; her followers are no longer derided as an “army of skanks.” Even the infamous Burn Book is now nicer — or, if not exactly nicer, at least avoids particular rhetorical land mines: “fugly slut” is now “fugly cow.” Dawn Schweitzer, once a “fat virgin,” is now a “horny shrimp.” (Don’t ask me what a “horny shrimp” is. I texted my 17-year-old neighbor, Clover, to ask if I was missing something in teenspeak, who replied, “HAHAHA IVE NEVER HEARD OF THAT” and then promptly texted her friends, who also didn’t know.)

This is meant to be reflective of the real world, of course, where ostensibly we no longer say these words, where we accept all body types (yeah, right) and have learned to be attentive to people’s feelings, differences and “residual trauma.” But what the movie misses, by simply stripping out the nastiest language, is a chance to really update itself — to fully reflect on girl world in 2024. Because if the hallmarks of relational aggression are things like cutting friends out, spreading rumors or exclusion, today’s technology has created innumerable new ways to enact that adolescent torture. The movie doesn’t ignore the internet — when Regina falls on her face in the talent show, she goes viral, sparking a TikTok challenge — but it doesn’t fully capture the way it functions among real teenagers.

So what does this stealth meanness 2.0 actually look like? I asked teenagers to tell me.

I’m the wrong age for the original Mean Girls to have hit with me. But I’m the mom of a teenager and we’ve been curious about how this update went. Thanks for the great analysis.