How Not to Apologize

Everyone seems to be sorry for something these days. A case for apologizing well.

You’re reading Wait, Really? — a newsletter unpacking what's in the culture, with a feminist spin. Want to get it in your inbox? Sign up below.

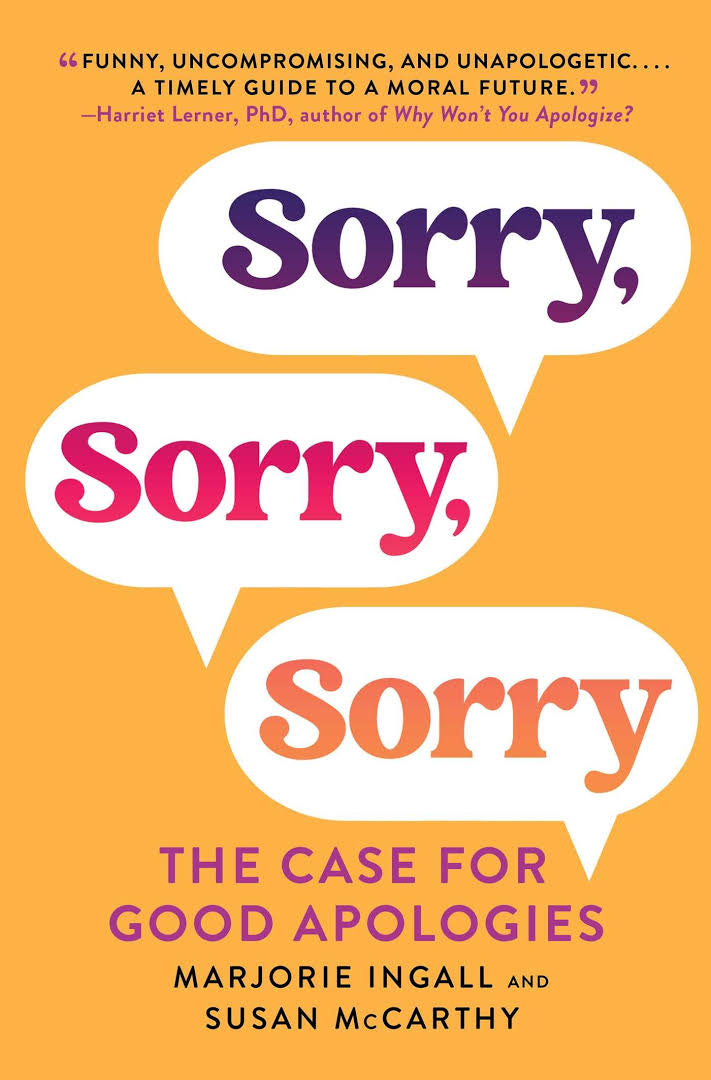

When longtime pals Marjorie Ingall and Susan McCarthy started a blog tracking public apologies a decade ago, it seemed the word “sorry” was having a moment.

This was the heyday of the political sex scandal: Anthony Weiner had been caught sexting with underage girls; Eliot Spitzer was linked to a high-end prostitution ring; Mark “I was hiking the Appalachian Trail” Sanford, former governor of South Carolina, tearfully admitted to cheating on his wife after turning up with another woman in Argentina.

Ingall and McCarthy, both writers, had long been fascinated by the art of the apology. But it was when Ingall’s daughter was in preschool — and, incidentally, spent most of her time in the punishment corner — that she really began to think about the function of the word “sorry.” Was there something all these constantly sorry public figures — and their ill conceived, insincere apologies — could learn from a 2-year-old?

The answer was — and still is — yes, though it seems few were truly committed to the lesson. These days, the public apologies are seemingly too numerous to count. A celebrity apologizes for misspeaking (then misspeaking again); a corporation apologizes for a mass inconvenience (here’s looking at you, Southwest Airlines), before having the same exact problem again. If everybody is apologizing all the time, what does an apology even mean?

In their new book, Sorry, Sorry, Sorry: The Case for Good Apologies, Ingall and McCarthy write a lively history of the apology, and unpack why a good apology is so hard to find. They also offer a step-by-step guide for how to apologize well (we need it!). I chatted with them about the book, out now, and the recent celebrity apology that made them want to scream.

Jessica: Talk to me about the utility of the apology — why should people apologize?

Marjorie and Susan: There’s a Talmudic term for repairing the world: tikkun olam. Good apologies can help repair a broken world. Good apologies save relationships! They make us feel connected to one another. They build and maintain trust. It also turns out that people really care about apologies. People hate bad apologies, even when they aren’t sure what's wrong with them. And yet they may not know what a good apology even looks like.

It seems like you can’t read the news these days without hearing about yet another public apology for yet another stupid thing a person has said. Do we have a precedent for all this public apologizing?

Public apologies go way back in history, though not necessarily by that name. Some of the earliest public apologies were in a religious context and took the form of doing penance publicly: Kings dressed in rags and walked miles to cathedrals to confess their misdeeds and pledge to do better. Other apologies were from one ruler to another or one government to another. Back when dueling was popular, experts codified the practice of apology as a way of not having to fight a duel. But now, with social media, so many people hear about misdeeds so fast that people are rushing out there with apologies — usually bad ones, and often so terrible that now they also have to apologize for their apology.

Right. It feels like the public apology has become meaningless.

We are entitled to expect public apologies because we deserve to see that those in positions of power know that they screwed up — and we deserve to hope that they will do better. But good public apologies are so rare because apologies made by celebrities, politicians, or corporations are usually about damage control, not repentance. They’re about placating customers, or fans, or shareholders, with the primary goal of getting everyone to move along as quickly as possible. There’s little motivation or incentive for any real introspection; why should a public figure do that work (if they’re even capable of that work) when the news cycle generally just trucks merrily along? Apologies motivated by capitalism don’t tend to be good apologies.

What’s a recent public apology that made you cringe?

Jeremy Clarkson, a British TV personality, wrote a column for The Sun about his hatred — “on a cellular level” — of Meghan Markle. He compared her to Rose West, an actual British serial killer, and said he was “dreaming of the day” when she was “made to parade naked through the streets of every town in Britain while the crowds chant ‘Shame!’ and throw lumps of excrement at her.” Apparently, this is a reference to Game of Thrones. People were, unsurprisingly, distressed by what Clarkson wrote, and he tweeted fustily that “I’ve rather put my foot in it” with a “clumsy reference” and “shall be more careful in future.”

This is what we term an “apology-shaped object” — a thing that has the vague contours of an apology but that does not, in fact, do any of the things an apology is supposed to do. Clarkson doesn’t use the words “sorry” or “apologize”; he doesn’t take responsibility for his actions; he doesn’t indicate that he knows what he did is wrong or why he caused hurt. Saying his column “has gone down badly with many people” blames readers. He notes that he’s horrified that people are upset, but fails to acknowledge that he himself upset them.

So how does a person apologize well?

The steps to a good apology are easy, but actually doing them is hard, because we’re wired to be defensive and to blame others. We believe the good apology has six parts — maybe six and a half.

Say you’re sorry. (Literally say, “I apologize” or “I’m sorry.” So basic, yet so often overlooked.)

For what you did. (Be specific. Name the offense.)

Show you understand why it was bad. (Acknowledge the impact.)

Only explain if you need to; don’t make excuses.

Say why it won’t happen again.

Offer to make up for it. (Six and a half: Listen.)

Read more about how to apologize — with tips on exactly what to say — in Sorry, Sorry, Sorry, out now.

Your post encouraged me to tell a lot more of the truth this week in my apologies. For example, I said it's my own fault that I got up too late to take the ice off my window. Not I was running late for some better reason Etc

Great content