The Last Remaining Courtroom Artists

Meet the women shaping the image of Donald Trump at trial.

You’re reading Wait, Really?, a newsletter about gender politics and cultural musings. Want it in your inbox? Sign up below.

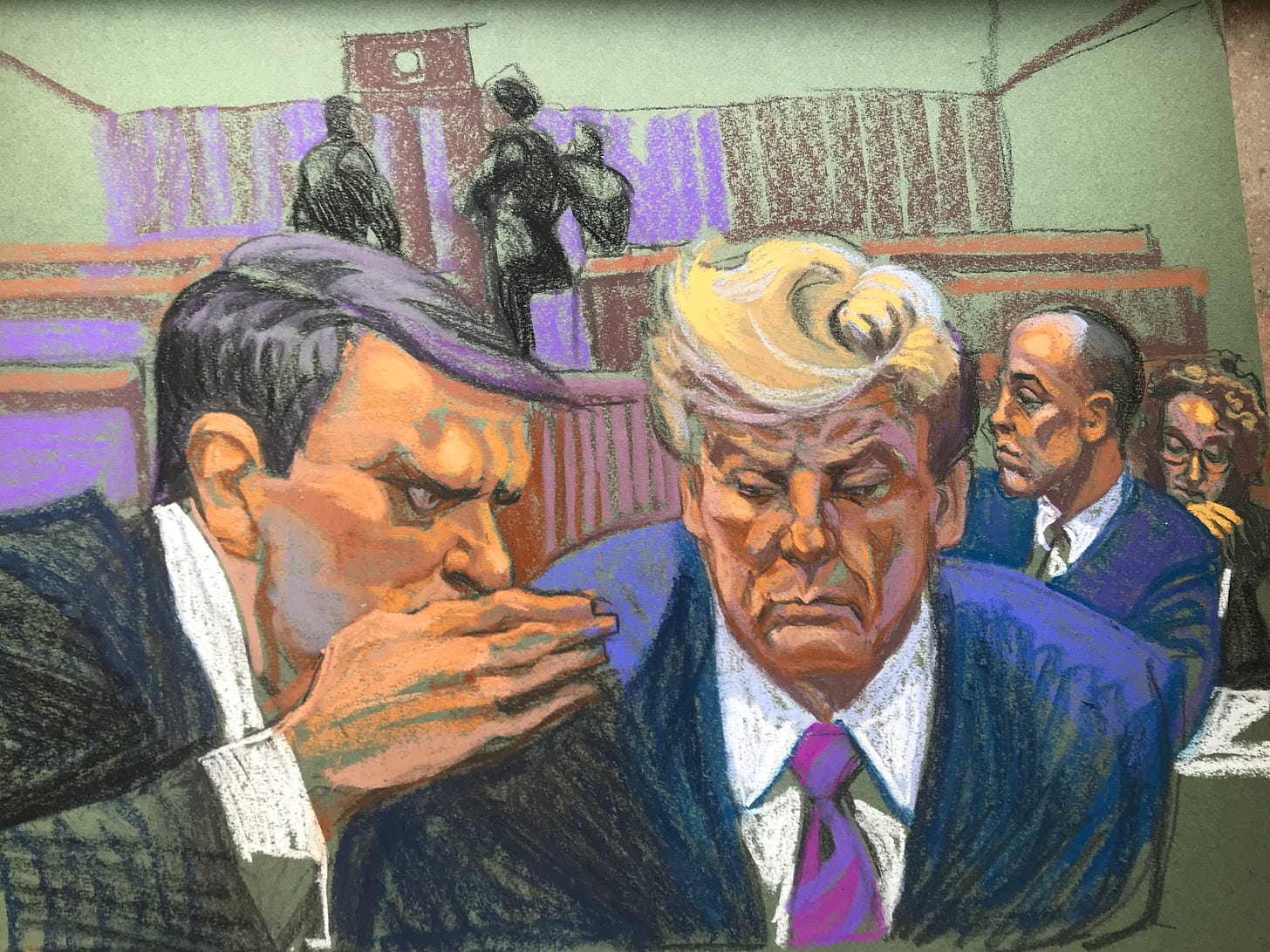

Christine Cornell was in a black patterned blouse and headband, her long white hair hanging over a pair of binoculars she was using to peer at the side of Donald Trump’s face. His cheeks were crinkling in a way she wanted to capture, his eyebrows furrowed into a scowl that made them protrude from his forehead almost “like a shelf,” she said. His hair was looking particularly lemon meringue-like, and she was studying its swoop.

It was the 13th day in criminal court, where Trump is on trial for paying off a porn star and falsifying business records to do it, and Cornell, a courtroom sketch artist who is drawing the trial for CNN, had just learned that Stormy Daniels would be testifying.

Trump’s criminal trial is not being broadcast on television, and there are no cameras allowed inside, which is why each day, throngs of reporters and and sketch artists and members of the public line up at dawn to try to get a seat in what’s called the “overflow room” — a crowded room with fluorescent lights, where we crane our necks to see what’s happening on a large television screen that broadcasts from the actual courtroom down the hall.

In that courtroom, where a small number of pre-approved journalists and four sketch artists sit, a handful of photographers are let in for 45 seconds each morning to photograph Trump at the defense table, during which time he leans forward and poses, putting on a scowl.

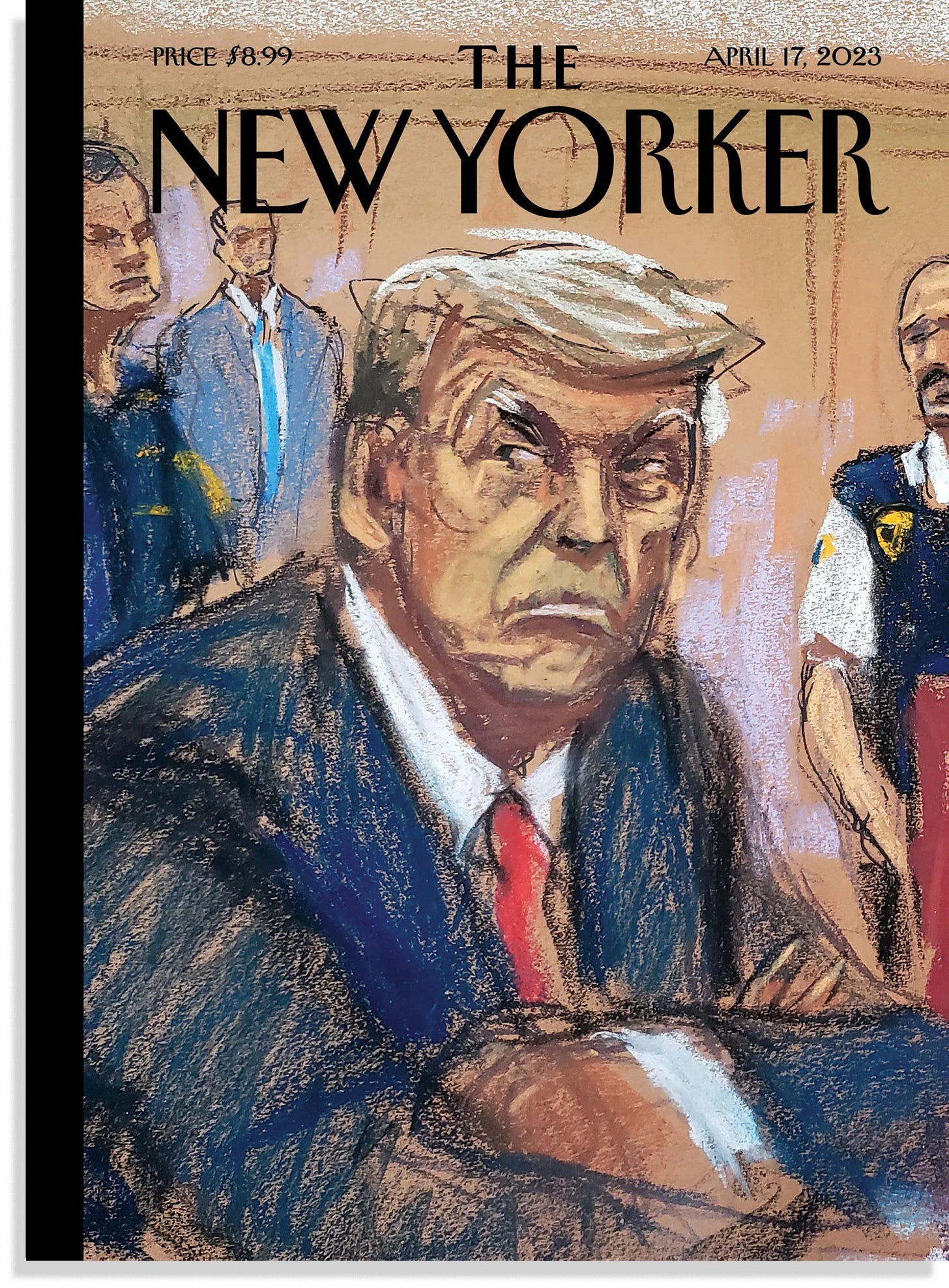

But then, one of them broke a rule: they photographed Trump from the side. The photographers were banned. Suddenly, the image of the first presidential candidate to be criminally tried — in arguably the most important political case in U.S. history — was entirely in the hands of the courtroom sketch artists.

I had no idea that courtroom artistry was even still a thing until I found myself seated behind the women above during the E. Jean Carroll sexual assault and defamation trials, mesmerized by watching them work. Clad in cat-eye glasses and drapey scarves, with wiry disheveled hair and fingers stained in chalk, the women — and it was only women — were a jarring sight against the masculine stiffness of the courtroom; the sound of chalk against paper at times the only audible noise amid tense silence.

There, I watched as Cornell, 69, used a forward stroke to capture Trump’s hair with a faded yellow pastel; she had been studying its curve. I saw Jane Rosenberg, 73, use opera binoculars to peer at the side of Trump’s face, slicing dramatic shadows into his cheekbones. Elizabeth Williams, who won’t tell me her age, but says she’s a decade younger than the others (so, 50s?), scribbled with a pen as Carroll testified, rotating between cardboard sketch boards she balanced on her knees, and producing an image — face agonized, hands raised — that reminded me of Munch’s “The Scream.”

Behind them sat a mother-daughter duo, Shirley and Andrea Shepherd, who like the others are something of legends in the insular room of courtroom sketch artistry — and have been in the business for some 40 years. As I peered over their shoulders, one of them remarked that she’d drawn Trump’s lawyer, Joe Tacopina, ages ago — and boy had he “had a lot of work done.”

These women were a side show to the main event, but one I couldn’t stop thinking about. What could they see that the rest of us couldn’t? How did it come to be, that the last remaining courtroom artists — in a field that, while it was never exactly bustling, once had dozens and dozens of artists, working for every major news outlet — was now just a handful of women supposedly past their prime?

There was something intriguing about the fact that the public was watching the Carroll trial, and now Trump’s criminal trial — each cases about misogyny and power — solely through the eyes of older women. Could they, I wondered, see themselves in Carroll, or even Stormy Daniels, in a way that imbued their sketches with just a touch more resolve?

It is a strange relic of a job, and one that exists because cameras are banned in most federal and New York courtrooms. Back when these women began their careers, there were many artists like them, churning out courtroom portraiture for outlets like Reuters, AP, the New York Post and The Daily News; Newsday, the local TV stations, and on and on. “If this trial took place 40 years ago, you would have three rows of court artists,” said Williams. Some carried hair dryers to set their watercolors in time for deadline; many used binoculars or wore opera glasses, and had rolls of toilet paper to clean the chalk off their fingers.

But as the news business has shrunk, so have the artists. And yet their jobs at this moment have perhaps never felt so significant, at least to the rest of us. They are our eyes inside.

Courtrooms make for great theater — full of raw emotion, tension, Oscar-worthy performances, with lives and reputations are stake. But that doesn’t mean the job of drawing it is glamorous.

The sketch artists rise around 5am, line up outside by 7am, then wait, sometimes for hours, to be let into the courthouses. In colder seasons, their feet are “blocks of ice” by the time they arrive, their fingers “numb to the first digit,” said Cornell. (This trial, she said, is cake compared to El Chapo; there they often had to line up overnight.)

Once inside, the artists work at a frantic pace, producing multiple sketches throughout the day, often with just a few minutes to nail each one, and under immense pressure not to miss any of the critical moments. When a sketch is ready, they climb over each other along the narrow wooden benches, trying not to make a sound, in order to quietly race out of the room, retrieve their cell phones and photograph the drawings to send in — often only to be mocked viciously online by the time they emerge from court.

The days are long, and the work is inconsistent, and increasingly so. Williams supplements with wedding sketches; while Rosenberg draws landscapes. Cornell, who comes from a family of journalists — she followed her reporter sister to court back in the 1970s and never looked back — says friends often ask if she plans to retire. She doesn’t, though for a brief moment when she heard that Harvey Weinstein was going to be retried, after his conviction was thrown out last month, she considered it. “I’m like, ‘Really?’ I have to go draw that mug again?”

I later ran into Cornell in the ladies room of the courthouse, where she had propped her image of Stormy Daniels up on the peeling radiator. This is where the artists flee during breaks, I learned, to take photos of their drawings to send in to their editors: Cornell on the radiator; Rosenberg on the trash dumpster.

“There’s something very gonzo” to it all, said Isabelle Brourman, a fine artist who has been sketching her way through the trial alongside the women, and has gotten to know them. “I’m always kind of shocked by their toughness.”

The women will tell you that drawing Trump is “like any other day.” They are casual about it, nonchalant, just doing their jobs and going home at the end of the day, as they have for more than four decades. That airiness — not indifference, but professionalism — makes a little more sense when you get them to start telling stories about the other things they’ve drawn.

The women have locked eyes with murderers, baby killers, rapists, mafiosos, the famous and infamous alike: Bill Cosby. The Central Park Preppy Killer. The “subway vigilante” Bernie Goetz, who shot four unarmed black teenagers on the 2 train in the 1980s and, Cornell learned, lived only a block away from her when he did.

Rosenberg was seated just a few feet away from Wadih Wadih El Hage, Osama bin Laden’s personal secretary, on trial for terrorism, when he lunged at the judge — before being tackled by U.S. marshals and dragged away bleeding. “He lept like Tarzan,” she said at the time. “I was shaking.”

Cornell was once asked out on a date by another terrorist, Ramzi Yousef, who was on trial for the 1993 World Trade Center bombing, and wanted to know if she’d go out with him if he beat the charge. (She declined, and he was convicted). “I figured he's going to be in jail forever, so why make his life more miserable?” she told Newsday, which described her in the paper as a “statuesque blonde.”

The women have been asked to fix hairlines, to be kind to skin (Martha Stewart to Cornell: "No pockmarks, perfect skin. Right?") and to “make me look sexy,” as Donald Trump Jr. requested during his father’s civil fraud trial. During Ghislaine Maxwell's 2021 trial on sex-trafficking charges, Rosenberg noticed something peculiar: that while she was sketching Maxwell, Maxwell was sketching her.

“You know, it’s a very weird life,” said Cornell, when I visited her at home in New Jersey. She was giving me a tour of her studio, where she has nearly five decades of courtroom sketches filed away in boxes. I learned later that she had played herself in "The Bonfire of the Vanities," the movie adaptation of Tom Wolfe's famous novel.

“Sometimes I'm almost embarrassed about it, because you think about all the other options in life,” she continued. “But I really fell into something that I'm good at and that I love to do.”

Cornell was pleased when I visited her that she had managed to capture Trump’s hair that week. She’d been studying it, she said: how it falls, the exact point where his part begins, the way it sweeps across his head, with golden highlights, and it interact with his eyebrows, which protrude so far from his head they cast a shadow. But the hair — well, the hair is “like the gilded carriage that takes Cinderella to the ball,” she said, in a description so perfect I may have it framed. “There's just an exaggerated peculiarness to it.”

I like to think of Cornell and the other women like detectives — of human nature, of our own vanity, of facial expressions and body language, interpreting the delicate dance of courtroom drama that plays out behind their brushstrokes so that the rest of us can understand it just a little bit better.

When Trump folds his arms, for instance — and he doesn’t do it a lot — you know something is bugging him, like really bugging him, Williams told me. His mouth, when it gets annoyed, starts to not purse exactly, but turn into a tight-lipped pout. Williams likes to draw his “accordion hands,” which is how she describes the way he moves his arms in and out when he speaks, like he’s playing an accordion.

Cornell was hesitant to draw him sleeping early on, she said, because well, who hasn’t fallen asleep in court? “It’s a very human thing,” she said. You know, the privation, the monotony.” With time, however, the women have come to recognize the difference between sleeping sleeping — eyes closed, chin drooped, eyes fluttering in their sockets — and just resting sleeping, with the possibility for his eyes to jolt open at any moment if he hears something he doesn’t like. “He’s like one of those wild animals in the bushes,” Williams said. “You think they're sleeping, but they'll jump up and chew your head right off.”

Sometimes they formulate hypotheses about him: Could it be a cataract that’s causing him to shut his eyes so much? Is he sensitive to light? But mostly, their job is to draw what they see — no editorializing, no infusing meaning or politics, just the facts. “I don’t want to pick on them,” Cornell says of her subjects. “I want to hold them to account.”

Both Cornell and Williams have drawn Trump before, back in the 1980s when he owned a football team in New Jersey and sued to force a merger between the NFL and USFL. In that case, Cornell told me, Trump dubbed her his “personal courtroom artist” — because she’d drawn a handsome portrait of him, and also “because I was young and cute,” she added with a wry smile.

He still has handsome features, Cornell says, but they have taken on a different quality these days: It’s not just “bravado and all that youthful stuff” but anger: “An intense, deep-seated fury.”

[[[You can read more about the Sketch Ladies in The New York Times here]]

Thank you so much for this Jess, I’ve been dying to know more about these artists

Hi Jessica,

Loved this piece ! Such interesting insights to the thoughts of these artists. I have a friend here in Las Vegas who has done some courtroom sketching for high profile cases. He is a terrific sketch artist but not of the same caliber as your gals. He didn't do it for a living. Anyway, I will forward your article to a couple of friends who will enjoy it.....I am sure. Barbara