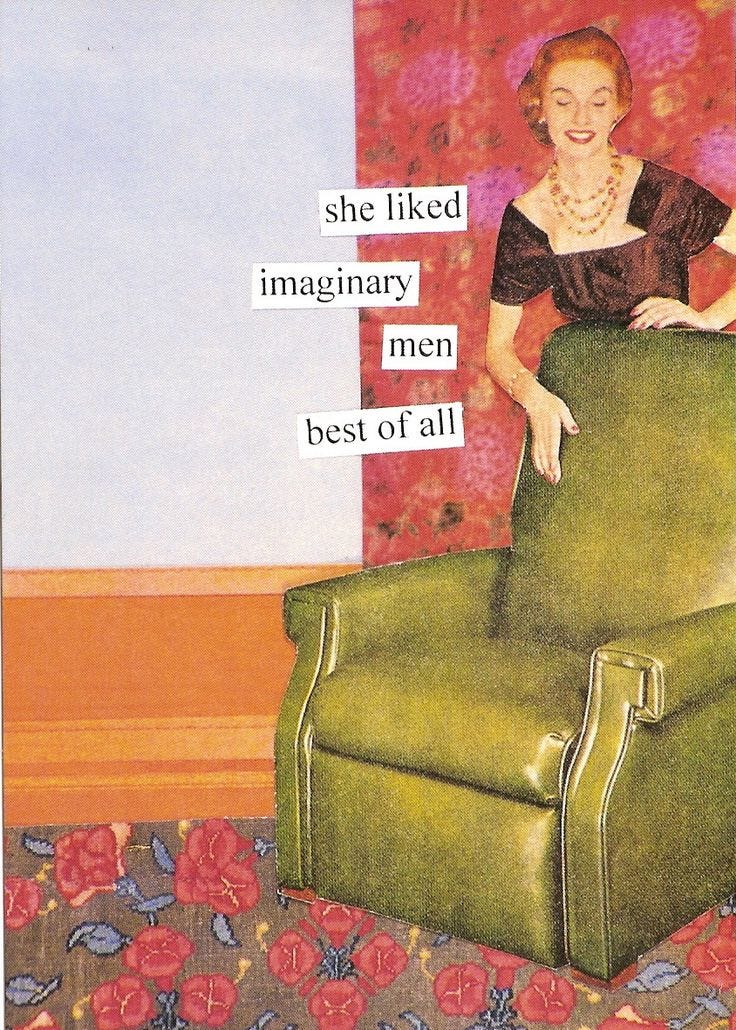

Wait, what's an 'Imaginationship'?

We're together... you just don't know it yet. Or so says TikTok.

This is a special edition of Wait, Really? written by Maria Clara Cobo, a recent graduate of the journalism master’s program at NYU and a former student of mine. She wrote this piece about young people and “imaginationships” last semester that I’ve been thinking about it in the context of the loneliness epidemic ever since. Enjoy, and please tell us what you think in the comments! —Jessica

WHEN SIENNA, 24, ordered the Tunisian pita sandwich at a sidewalk cafe in Brooklyn, she immediately thought that her boyfriend, Jack, would love it.

Jack is tall and blonde. He works in banking but still manages to text Ross at every hour of the day, especially after her stand-up comedy shows. Jack believes in God but is not intensely religious. He’s funny and likes to buy flowers for his girlfriend — lucky her. He’s the ideal partner, almost too good to be true perhaps because he is. “Jack” in fact does not exist.

Jack is Ross’s imaginary boyfriend — “imaginationship,” if you follow the lexicon of TikTok. That means that even though Ross doesn’t actually receive text messages or flowers from anyone, she explores the qualities she would like in a future partner by fantasizing about someone who is not real. And, perhaps not surprisingly for someone of her age, she broadcasts her experience in a series of videos, where she is almost jarringly honest about the intensity of her feelings for a person she has created in her head.

“I made up this perfect person in my head by taking aspects of different people I’ve seen,” Ross told me in an interview. “Obviously, I don’t really know a ‘Jack,’ but after a while, the idea of him has fixed my itch for a relationship because I am getting the storyline of a person I would like out of my system.”

Ross did not create the idea of the “imaginationship.” On TikTok, anyway, there are thousands of people who fantasize (and post) about relationships that don’t actually exist. Some make videos about planning a wedding registry and guest list, naming their future children, looking up houses in Connecticut on Zillow. One person, a poet, wrote a piano ballad about her imaginary boyfriend. The lyrics: “There's a subconscious part of me that wants to preserve the delusion, so there must be a conclusion, but you're my obsession!"

The #imaginationship hashtag has some 30 million views. But the idea has apparently been around at least since 2009, when Urban Dictionary defined it as “an almost nonexistent relationship, usually of a romantic nature, with one party exaggerating or imagining their closeness.”

The key word there: almost. Unlike Sienna’s Jack, who is entirely aspirational, many of the imaginationships I explored on the platform — and the people I spoke to who engaged in them — describe the subjects of their yearning as real people: either someone the dreamer has seen but hasn’t met yet, or possibly someone they did meet, or even went out with, but never saw again. Even though people know the relationship isn’t real, sometimes they’d rather keep it that way to maintain the illusion of a person.

Libby Ebert, a clinical associate at Embrace Sexual Wellness, a Chicago-based wellness center specializing in relationship wellness, explained the psychology of such an urge this way: “In an imaginationship, a person is in a perpetual state of limerence — a state of profound infatuation and romantic longing that characterizes the beginnings of a crush,” she said. “I’ve had many patients tell me they particularly like the beginnings of liking someone versus getting to know them and bursting their bubble.”

The experience of catching oneself fantasizing about a crush — or even wishing one was more like how you imagined them than how they end up to be — is highly relatable. But weren’t daydreams supposed to be private vessels for secret lives and hopes that nobody else could touch?

Maybe. And yet 73 percent of Gen Z report feeling alone — a statistic that parallels the American decline in sex. More than a quarter of Americans hadn’t had sex at all in the past year, according to the General Social Survey in 2021 — the highest level of sexlessness in the survey’s history.

Perhaps at the heart of an “imaginationship” lies the fact that more people are not dating, talking, hooking up, or possibly even texting their love interest — or even their friends. If you can create the perfect partner in your mind, why put yourself out there to find a real one?

Ebert, the relationship counselor, notes that “there’s nothing unusual or creepy about having some sort of imaginationship”; in fact, TikTok and Instagram can be great place to be vulnerable about an unfulfilled longing. But, “I worry about how much imaginationships can be a way for people to avoid getting hurt.”

“People might not realize it but they can also be inadvertently hurting themselves by not creating meaningful connections,” she said.

Which isn’t to say that the fizzling out (breakup?) of an imaginationship can’t be painful on its own. Erin Gibney, a 23-year-old singer from Nashville, recently posted a video describing how she felt when she saw the guy she was in an imaginationship with — a real person she had a crush on — began posting photos of another girl on his story. “Will I get over it?” she asks the camera in the video. After a brief pause, she rolls her eyes and replies: “No, but life goes on.”

Meanwhile Sienna, the stand-up comedian, decided that one of her New Year's resolutions was to stop wasting her time dating people who did not want to be in an exclusive relationship. In the past, she said, she dated men who did not care for her, who ghosted, who even cheated. That’s why she created Jack.

“I wanted to relinquish all of my shitty situationships and start thinking about someone I want in my life,” said Ross. To her, Jack was no longer just an imaginary person, but a concept that embodied the kinds of behaviors she looked for in a man.

“I remember seeing a man carrying a bag of roses on the street and thinking, ‘Wow, that’s so Jack.’”

A few weeks later, as she was preparing for a comedy show, a tall, blonde Belgian man approached her. They talked for a while—he already followed her on Instagram and was a fan of her comedy. A few minutes later, he DMed her asking her out for dinner. Such a Jack moment.

“I haven’t seen enough of this guy to proof that he’s Jack, but since I created Jack I’ve had more positive encounters with men than ever before,” she told me. “Jack is my North star when it comes to dating. I credit all these magical moments that seem taken from a movie to him—he did this for me.”

Maria Clara Cobo is a writer and editor based in New York City. She has been published by The New York Times, CULTURED, Forbes, and Sentimental Journal. You can read more of her work here.

Women have always fantasized about their ideal partner, but it’s interesting trying understand why we are now settling for living with that ideal, instead of gettign out there and meeting real men.

When you turn 40, and have been through few major emotional disspaintments, you are certainly afraid of getting hurt again. It takes some effort to invest that emotional energy on finding the right person to share your life with, supspecting your expectations might get schattered once again.

It takes a lot of digning to find Mr. Right.

But… That’s the problem! Mr. Right as the ultimate goal of our emotional happiness.

And Mr. Right as the embodiment of our new expectations in men.

Nowdays, women have economic indpendency and higher standards when it comes to date. We are re-shaping the whole dating scene and narrative, and posing many questions to the traditional masculinity.

All these issues are incredibly interesting to research and debate under the light of our new agency.

Despite finding someone is totally a legimitate wish to fulfil… Why are still so focused on that narrative: Be happy forever after when you find the One?

https://youtu.be/S4cpa-o4QdQ?si=Z6u2PJlXq5x2HVOS